Cost-Output Relationship

The cost-output relationship plays an important role in determining the optimum level of production. Knowledge of the cost-output relationship helps the manager in cost control, profit prediction, pricing, promotion, etc. Output is an important factor that influences cost. Considering the period, the cost function can be classified as:

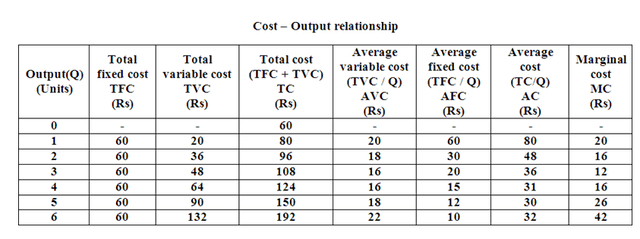

Under the short-run cost-output relation, costs are classified into fixed costs and variable costs. Labour is the variable factor while capital is the fixed factor. Total fixed cost remains constant while variable cost changes with the variation in units of labour. The fixed costs may be ascertained in terms of total fixed cost and average fixed cost per unit. The relationship of costs in the short run can be summarized as follows:

– Total fixed costs remain fixed irrespective of the increase or decrease in production activity.

– Average fixed cost per unit declines as the volume of production increases due to spreading fixed costs over more units.

– Total variable cost increases proportionately with production.

– Total cost increases with the volume of production.

– Average total cost initially decreases up to a certain level of production, then rises, forming a U-shaped curve.

– Marginal cost reflects the change in total cost due to one unit change in output.

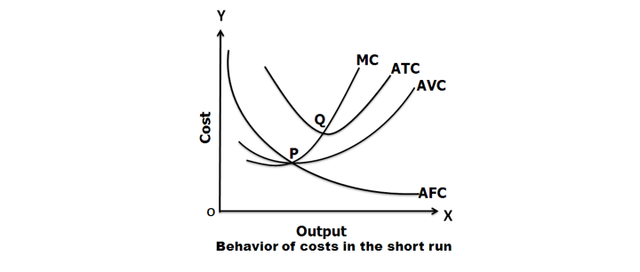

The short-run cost-output relationship can be illustrated graphically as follows:

– The Average Fixed Cost (AFC) curve slopes downwards continuously as production increases.

– The Average Variable Cost (AVC) curve is U-shaped, initially falling and then rising due to the law of diminishing returns.

– The Average Total Cost (ATC) curve initially declines with AVC but rises after a certain production level.

– Marginal Cost (MC) initially decreases with output but later increases steeply.

Long run refers to that period of time over which all factors are variable. It has no fixed cost. Over a long period, the size of the plant can be changed, unwanted buildings can be sold, staff can be increased or reduced. The long run enables the firms to expand and scale their operation by bringing or purchasing larger quantities of all the inputs. Thus, in the long run, all factors become variable.

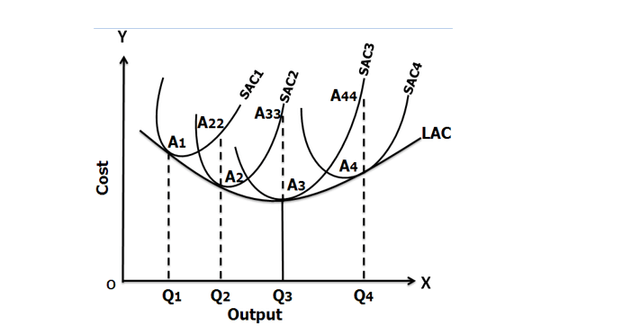

In the long run, a firm has a number of alternatives regarding the scale of operations. For each scale of production or plant size, the firm has appropriate short-run average cost curves. The short-run average cost (SAC) curve applies to only one plant whereas the long-run average cost (LAC) curve takes into consideration many plants.

If we assume that there are many plant sizes, each suitable for a certain level of output, we will get many SAC curves intersecting each other. As the number of plant sizes increases, the points of intersection of SAC curves will come closer. And, if we assume that there are a large number (say, an infinite number) of plant sizes, the intersection points will be so near to each other that we get almost a continuous curve. This continuous curve is known as the Long-run Average Cost (LAC) curve or the Envelope curve (as it envelopes the family of short-run Average Cost Curves).

The long-run cost-output relationship is shown graphically with the help of the LAC curve.

The above figure shows how the LAC curve envelopes several short-run average cost (SAC) curves. Suppose, the firm is producing an output of OQ1 units on a plant of SAC1, if it wants to produce OQ2 units of output, either it can operate on SAC1 by over-utilizing the SAC1 plant or by acquiring a bigger size plant SAC2 and operating on it. It will be less costly to operate on SAC2. If it wants to produce OQ3 units of output, it can operate on the bigger size plant SAC3 at least cost. Q3A3 is the least cost at the output OQ3 and the firm attains optimum output in the long run at OQ3 level of output. If it operates on SAC2 to produce OQ3 units of output, the cost will be prohibitively high being Q3A3. It is to be noted that there is only one short-run average cost curve SAC3 which is tangential to the long-run average cost curve at its minimum point. All other SAC curves are tangential to the LAC curves at higher than their minimum average cost points.

Law Of Demand

Law of demand shows the relationship between the price and quantity demanded of a commodity in the market. In the words of Marshall, “the amount demanded increases with a fall in price and diminishes with a rise in price.”

The law of demand states that “other things remaining constant, the higher the price of the commodity, the lower is the demand, and the lower the price, the higher is the demand.” This is called ceteris paribus (Latin phrase meaning other things constant).

The law of demand may be explained with the help of the following demand schedule.

When the price falls from Rs. 6 to Rs. 5, the quantity demanded increases from 1 to 2. In the same way, as the price falls, the quantity demanded increases. On the basis of the demand schedule, we can draw the demand curve. The above demand curve shows the inverse relationship between the price and quantity demanded of apples. It is downward sloping.

Assumptions:The law of demand is based on certain assumptions:

There is no change in consumers’ taste and preferences.

Income should remain constant.

Prices of other goods should not change.

There should be no substitute for the commodity.

The commodity should not confer any distinction.

The demand for the commodity should be continuous.

People should not expect any change in the price of the commodity.

Exceptions to the Law of Demand

According to the law of demand, other things being constant, as the price increases, the demand for the commodity decreases and vice-versa. But this is not true all the time. In some cases, as the price increases, the demand for the commodity will also increase, and the demand decreases when the price decreases. All these cases are considered exceptions to the law of demand.

When the price increases from OP to OP1, the quantity demanded also increases from OQ to OQ1 and vice versa. The following are the exceptions to the law of demand:

Giffen goods or Giffen paradox:

The Giffen good or inferior good or cheap good is an exception to the law of demand. The demand for these goods varies directly with the variations in prices, i.e., there exists a direct relation between the quantity demanded and the price of the commodity. Giffen goods may or may not exist in the real world. Giffen goods are named after Sir Robert Giffen. He conducted a survey on American laboring families who consume bread and meat. The survey revealed that they spend more of their income on bread because it is their staple food or main food and less of their income on meat. When the price of bread increases, after purchasing bread, they don’t have surplus money to buy meat. So, the rise in the price of bread forced the people to buy more bread by reducing the consumption of meat and thus raised the demand for bread. Goods like bajra, barley, gram, millets, and vegetables fall under the category of Giffen goods.

Goods of status:

In some situations, certain commodities are demanded just because they are expensive or prestige goods and are usually used as status symbols to display one’s wealth in society. Examples of such commodities are diamonds, air-conditioned cars, duplex houses, etc. As the price of these commodities increases, they are more considered status symbols, and hence their demand gets raised. This goes against the law of demand.

Ignorance:

Sometimes, the quality of the commodity is judged by its price. Consumers think that the product is superior if the price is high. As such, they buy more at a higher price.

Consumer expectations of future prices:

If the price of the commodity is increasing, consumers will buy more of it because of the fear that it will increase still further. Similarly, if the consumer expects the future prices to decrease, he may not purchase the commodity thinking that the good may be of bad quality. This violates the law of demand.

Fear of shortage:

During times of emergency or war, people may expect a shortage of a commodity. At that time, they may buy more at a higher price to keep stocks for the future.

Necessaries:

In the case of necessaries like rice, vegetables, etc., people buy more even at a higher price.